On 18 April 2015 more than 1,000 refugees and migrants left Libya in an overloaded fishing boat bound for Europe. On a moonless night in the Mediterranean the vessel sank. But those who drowned are not forgotten – for the last five years a team led by an Italian forensic pathologist has been on a mission to name them.

“There’s a body that needs to be identified, you identify it – this is the first commandment of forensic medicine,” says Dr Cristina Cattaneo, professor of forensic pathology and anthropology at the University of Milan.

Cattaneo’s obsession is naming the dead. That is normal if a plane crashes in Europe, she says. Why should it be different for migrant travellers?

“There are so many tombstones in European cemeteries with ‘unknown’ written in Italian in place of a name, and the date of death. And that’s it. I think this is tragic. It’s the ultimate insult that someone can receive.”

Cattaneo and her team have opened files for more than 350 missing persons whose families believe they may have died on the shipwreck of 18 April 2015.

“This means 350 families have approached some sort of authority looking for their dead in this incident. Five years have gone by and these people are still looking for their loved ones,” she says.

The people who got on that old boat in Libya came from a dozen African countries, including Senegal, Mauritania, Nigeria, Ivory Coast, Sierra Leone, Mali, Gambia, Somalia and Eritrea. There were Bangladeshis on board too. The man steering the boat, a Tunisian, together with a Syrian, would later be convicted of manslaughter and human trafficking in an Italian court.

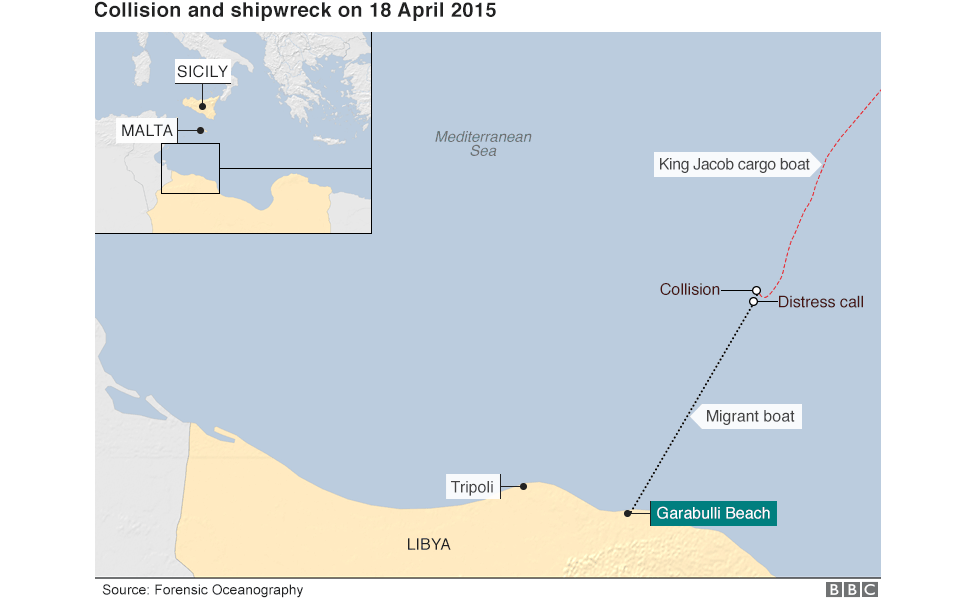

The ill-fated voyage began at dawn on the beach at Garabulli, east of Tripoli. A nameless 20m-long fishing boat, painted a jaunty sky blue, bobbed on the waves.

On its bow was an inscription in Arabic, “Blessed by Allah”.

Ibrahima Senghor had been waiting to get on the vessel since 3am. He had travelled from Senegal to this beach in Libya with other young men from his village, then in the milling crowd of hopeful passengers, he had become separated from them.

“We were in 10 groups of 100 people,” he remembers. “Seven of the groups boarded. I was in the eighth group. More people arrived in a refrigerated truck. They got on the boat too. We could see it was heavily loaded, and then the traffickers announced the boat was full. I said, ‘That’s impossible.’ I insisted I had to go too.”

But the people-smugglers would not let Ibrahima Senghor board. He had paid the equivalent of around $1,000 in local currency, but the traffickers prioritised those who had paid in US dollars. Ibrahima’s friends had boarded early on and probably descended into the hold. He was left on the shore with 300 others, watching the boat depar

“The boat pulled away. But then it turned around. The captain called out that they were overloaded. The trafficker just ordered him to leave – he said if the captain didn’t go, he would kill him on the spot. The trafficker drew his gun and shot into the air. Until 10am we could still see the boat in the distance.”

Travelling on the deck as the vessel headed for international waters, was Abdirisaq – one of 24 Somalis on board. Desperate to leave Libya, he and his friends had forced their way on at the last moment.

“I was so relieved because I was leaving the Libyan civil war behind,” he remembers

By 2015, after the fall of Muammar Gaddafi, power in Libya was dangerously fractured. Migrants were vulnerable to kidnap – they were often held hostage in horrific conditions and forced to pay large sums of money before being released.

Abdirisaq was not thinking about how seaworthy this vessel was – he knew he was taking a gamble.

“I wasn’t worried about safety,” he says. “I thought we’d have a 50/50 chance – we’d either get to Europe or the boat would sink.”

As they headed into open water, Abdirisaq fell asleep. By the evening, about 100km out to sea and still closer to Libya than to Italy or Malta, the boat began to take on water. The captain put out a distress call.

The European Union had pulled back on its search and rescue operations, so a merchant vessel was the first on the scene, at around 11pm. It was a pitch-black night, and the King Jacob – a huge container ship – switched on its lights. The shape of the small fishing boat was completely obscured by the hundreds of people crowded on the deck. The master of the King Jacob turned off his engines to commence rescue, and the overladen fishing boat attempted to pull up alongside.

The migrants’ boat was unbalanced by the on-deck passengers who panicked and moved towards the side of the boat closest to the King Jacob. And then – inexplicably – the captain accelerated.

“Our boat crashed into the large ship head on,” says Abdirisaq. “We hit the ship more than once. Then we scraped along its side. After that, we couldn’t stay afloat and we capsized.”

Abdirisaq – an excellent swimmer – found himself under the boat and under the water.

“When we were thrown into the sea, people were holding on to me. My clothes were ripped off as I tried to free myself and swim to the surface,” he says.

When he emerged, there was mayhem.

“I could hear a lot of shouting and screaming. People were still trying to hold on to me, so I swam away from the crowd – I was so tired, and I still had so much water inside me. I tried to swim after the big ship. I was about to give up, when they threw down a life belt.”

Utterly exhausted, Abdirisaq managed to climb the ladder up the steep sides of the King Jacob. He was one of only 28 survivors.

In the early hours of Sunday morning, Guiseppe Pomilla – a volunteer doctor – arrived in the darkness from Sicily on an Italian coastguard vessel.

“There was just a huge silence – nothing moved,” he remembers.

It was not until Pomilla boarded a small dinghy, bringing him closer to the surface of the water, that he was confronted with the sea of half-submerged bodies.

“There were so many, moving up and down with the movement of the waves.”

He and his colleagues grabbed at the floating bodies to see if anyone was still alive. No-one was. Then they heard a scream. With the aid of a lamp, they were able to locate the man and pull him on board.

“He was simply euphoric – he couldn’t stop talking. He asked me if I was Italian, and said that from today he would love Italy for ever.”

Pomilla helped rescue one other migrant that night.

“We thought he was dead. His eyes were open and he didn’t move. Then he grabbed my hand.

“Those two people we rescued… I always wonder if maybe there was someone else alive – somebody who couldn’t scream, or couldn’t move, so we never got to them.”

At the time, it was reported that 800 people had been on the doomed fishing boat, and in 2015, the loss of so many refugees and migrants still had the power to shock. There was an emergency meeting of European governments. Italy’s Prime Minister, Matteo Renzi, said they would seek to salvage the shipwreck, recover corpses and give them funerals.

Later, Dr Cristina Cattaneo got a call from the office of the Italian Commissioner for Missing Persons.

“There were 249 bodies collected around the boat. And we worked on these until a year after, when our prime minister decided to pull the boat up,” she says.

A task force was assembled – this was the first time a migrant boat would be raised from the depths of the Mediterranean.

Robots roamed the seabed, and the vessel was located at a depth of 370m. Italian navy divers placed a large wreath on the boat, before it was lifted using a specially built cradle.

On 27 June 2016, it broke the surface of a glassy Mediterranean Sea.

This feat of engineering cost 9.5 million euros (£8.6m). The boat was taken to the military base of Melilli on the island of Sicily, where an army of volunteer fire officers and forensic pathologists were waiting – including Cristina Cattaneo.

“I remember walking along the coast with the stray dogs, and seeing out of the corner of my eye this huge apparatus, which was the ship pulling the migrant boat,” she says.

“Our boat looked so small. And, due to the recovery, it had two huge holes in the sides which the Navy had covered with black sheets so nothing would fall out. And this image of mythological Greek ships coming back with black drapes when there was bad news just came to mind… It was a very strong moment.”

Over 12 days, 348 fire officers from the length and breadth of Italy were charged with removing the human remains from the sky-blue boat.

“Just imagine a floor which is covered with bodies,” recalls Cattaneo – bodies whose faces were no longer discernible after a year under water.

“They looked like dressed dummies. There were about five or six strata of bodies, one on top of the other. And I remember my first impression was that I had never seen – I could never have imagined – a similar scenario.”

This was new terrain for the fire officers too. Cattaneo gave them precise instructions.

“To be very careful to see what was connected. For example, if there’s a head and a torso, see if there’s any sort of tissue or string of tissue connecting them, and not to lose anything in the collection. We’re talking about bodies that are decomposed, very slippery.”

It was deeply upsetting work. In full protective equipment and with temperatures reaching 40C in the Sicilian summer, the conditions were brutal. The fire officers worked in 20-minute shifts, and were debriefed by psychologists in the evenings.

Meanwhile, Cattaneo and a team of pathologists worked on the autopsies.

“These individuals had all their documents sewn in their clothes. And therefore, we would have to carefully cut the lining of the clothes open, because in there you’d have documents, ID, letters, love letters – there was a report card of a 14-year-old. And I remember one of the first bodies – this 18-year-old had tied into his T-shirt a 2cm pouch of something that looked like soil.”

That is exactly what it was.

“And this hit me so hard, because this was what I used to do, too… I grew up in Canada, but I would come to Italy in the summer. And every year when I went back, I would fill my pockets with leaves from the country I loved, which was Italy. The analogy was so close for me.”

The autopsies threw up something puzzling.

“We only found one small child tooth and no child bones, which tells us there was at least one child on this boat. But the survivors talk about women coming on a truck and holding these children, these babies. And we have no personal belongings that hint at women. So for now, this boat is about two generations – adolescent and young, adult males.”

There is conflicting testimony about the presence of women and children on the fishing boat. Ibrahima Senghor, who never boarded and was left on the beach, says he saw them. But Abdirisaq, the Somali survivor of the shipwreck, did not remember seeing any females on deck.

The people traffickers filled every single space on the sky-blue fishing boat with human cargo. Even the bilge – below the hold and the waterline, and no more than 60cm high – was packed with the skeletons of adolescents. And the space where the anchor chains are normally stored was also occupied – there were dozens of bodies here too.

Some of the remains removed from the boat were buried in Sicily after being profiled by Cattaneo and her team of pathologists. And at the end of the summer up to 30,000 commingled remains – body parts hard to separate from one another – were transported to her lab in Milan.

“Imagine crania and every single bone of the body from 500 individuals being put in a big bag and then being shaken and poured out again,” she says. “That’s what we’re still dealing with now.”

The task of identifying the commingled remains gave Cattaneo a recurring dream.

“I was on a road with loads of gravel and pebbles and I was looking for tiny bones. At every corner, I would think I saw a bone, and then it was a pebble, and it went on and on like that.”

“The obsession derives from the fact that what remains from one of these individuals could be represented only by a phalanx – a very small bone [in the hand or foot]. Therefore, it could be the only way to identify that person. That’s quite stressful.”

For Cattaneo, naming the missing is important because these are human beings whose lives should be honoured, but it is also about those who are bereaved.

“Identifying the dead has to be done, not only to solve criminal cases or for respect for the dignity of the dead, but it’s something that has to be done for the health of the living,” she says.

“I think it’s easy to imagine that not knowing is worse than knowing that he or she is dead. If you have the certainty they’re dead, you can start grieving.”

In parallel with Cattaneo’s forensic work, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has gone in search of bereaved family members who believe their loved ones were shipwrecked on the night of 18 April, 2015.

“We don’t need only to wait for people to come to us, but also to go to them, to find out where they are searching for somebody and collect associated information for these individual cases,” says Dr Jose Pablo Baraybar, the Forensic Co-Ordinator of the ICRC, and a veteran of investigations and missing person inquiries in Srebrenica, Rwanda, and his native Peru.

Baraybar has been on field trips to Mauritania and Senegal to meet families who believe their relatives were on the sky-blue fishing boat, collect their DNA, and record interviews about the missing people – anything that might help in the process of identification.

He has also met witnesses like Ibrahima Senghor, who is back in Senegal now scratching a living after failing to board the boat in Libya.

“You will always find somebody that saw something, somebody that was actually in the same event and has survived,” says Baraybar.

“And that information is extremely useful to try to create in this specific case, some sort of passenger list. Now we have a few hundred names. It is a painfully slow process. So the first breakthrough was determining that the real number of people in the boat was between 1,050 and 1,100 people.”

This is roughly 30% more than the 800 estimated missing in 2015.

Ibrahima Senghor gave the ICRC information about missing friends from his locality of Kothiary, in eastern Senegal.

“There were three people I knew, one was my apprentice. Since the day we left home, we were always together – we spent a week in the desert, we were together until the moment we arrived at the beach in Libya,” he remembers.

Ibrahima Senghor had sold everything – including his oxen – to make the journey to Europe. On 18 April 2015 he was bitterly frustrated his friends had boarded the boat, and he had not. But when he heard the news about the shipwreck, he resolved to return to his village. It was a painful homecoming.

“I stayed in the house for two months without setting foot outside. Everyone thought I was crazy. I wasn’t crazy. It was because at first, I just couldn’t go out and face my lost friends’ parents and brothers. Still today when we see each other, we burst into tears,” he says.

Making contact with the families of the missing in their home countries is challenging, but Cristina Cattaneo thinks much more could be done in Europe. She believes many of the migrants would have had relatives who had already crossed the Mediterranean, or followed a land route to Paris, Berlin and London.

So she would like to see the creation of a network of offices across the continent where those seeking missing people – and not just the families of migrants – could go.

This would make it possible to compare data from the pathologists, like DNA and dental information, with material provided by friends and family of the missing person – ideally DNA, but it could also be X-rays, personal belongings, photos and descriptions of the person.

Cattaneo knows this can work because it has been done before. After two migrant shipwrecks in the Mediterranean in 2013, families of lost relatives were invited to Rome and Milan to be interviewed and provide data. More than 40 missing people were subsequently identified.

That is far more than Cattaneo and her team have been able to identify from the sky-blue boat that sank in April, 2015. In fact, more than five years since the disaster, only four of the dead have been officially named, their remains still buried in Sicily.

As a result of the ICRC field trips, there are genetic profiles for 80 families looking for loved ones. And Cattaneo and her team have collected post-mortem information from the human material taken from the boat for 150 of the bodies.

Cattaneo is exasperated by the slow progress.

Although the journey from North Africa across the Mediterranean Sea is the most deadly migrant route in the world with an estimated loss of nearly 20,000 people since 2014, Europe’s attitudes to migration have hardened, and money for her mission has become harder to obtain.

Cattaneo and her team have voluntarily continued to work on the human material collected from the boat, but they could work much faster if they could get the necessary funds.

She wants to create DNA profiles for all the remains stored in Milan. This, together with better collection of information and samples from families, would bring results, she says.

Abdirisaq, the young Somali man who lost his friends but survived the shipwreck of 18 April 2015, is trying to build a new life in northern Europe. He still lives with that hellish night.

“Sometimes I remember and I have flashbacks. I’m OK – thank God I survived. But what I went through on that boat, that’s not something I can forget,” he says.

Abdirisaq knew the boat had been raised from the Mediterranean’s seabed. But he was not aware of the efforts of Cattaneo and the ICRC to name all the people on board until he was contacted by the BBC.

“It’s exciting to know there are people who are trying to find out about my friends who died that day,” he says.

“It will help me if I know their remains were found. I will support the doctors however I can to help identify my friends.”

Abdirisaq also knows the identities of some of the other Somalis who drowned – more names to add to the passenger list of the sky-blue fishing boat.

“The dead tell you how they lived and how they died,” says Cattaneo.

“And how they died tells you what they risked, what they went through. They are immortalised in the moment of their worst fear coming true. I think it is important to know this. And if you see this, it changes you permanently.”